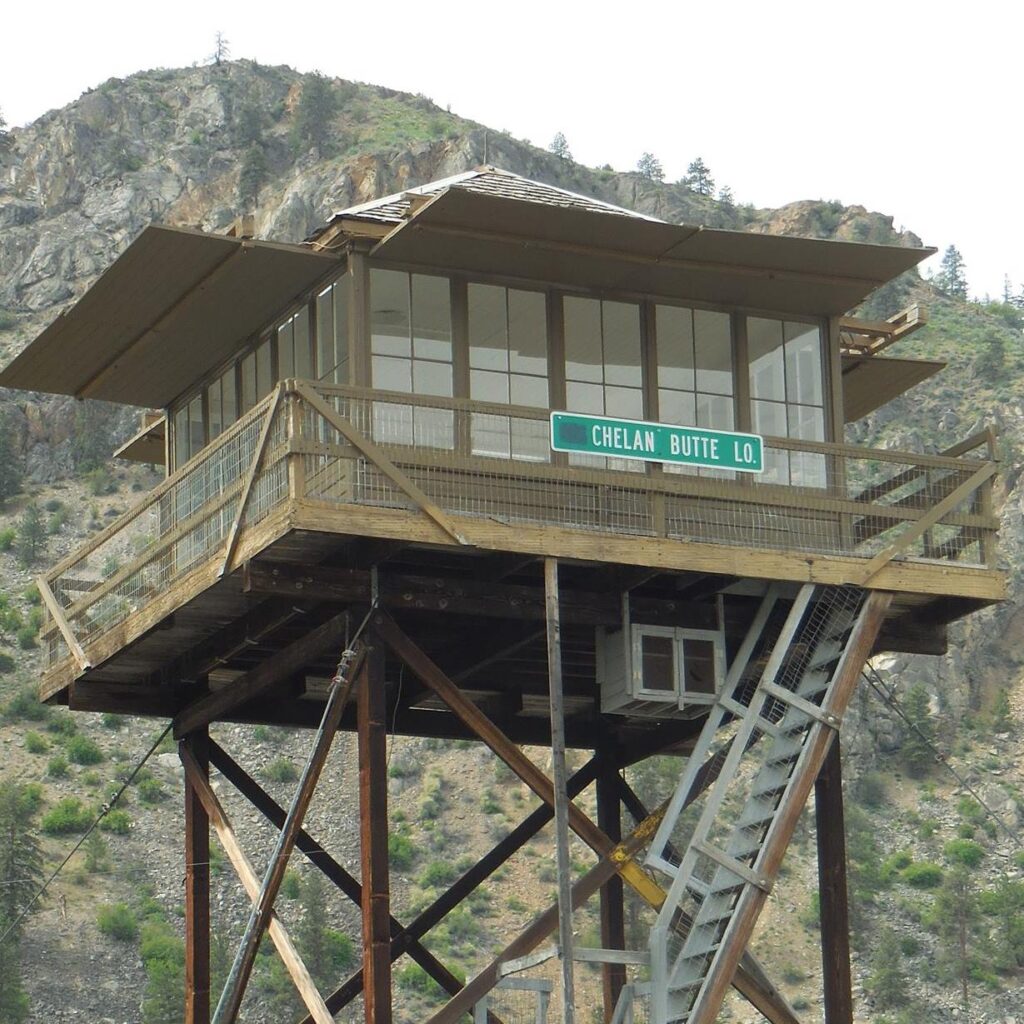

The Columbia Breaks Fire Interpretive Center near Entiat was first conceived as a way to relocate and save the Chelan Butte fire lookout. In 1990, Nancy Belt, an assistant fire dispatcher for the Wenatchee National Forest, received a Forest Service grant to study the feasibility of the idea and it grew into a much larger project. The Interpretive Center is now home to three relocated lookouts: Chelan Butte, East Flattop, and Badger Mountain, as well as a beautiful Firefighter Memorial Trail, an interpretive garden, and small amphitheater. The Center hosts a wide array of educational information about fire and plant ecology, fire behavior, history, and management, and has some nice fire memorabilia and displays.

Columbia Breaks is supported entirely by grants, private donations, and loads of volunteer time. I first visited Columbia Breaks back in 2017 during a visit to nearby Steliko Point lookout but it wasn’t until yesterday that I actually got to meet many of the folks responsible for this beautiful interpretive site.

Last year Columbia Breaks made a call for volunteers to help with restoration of the Badger Mountain fire lookout, built in 1941, staffed until the 80s, then relocated to the Center in 1999. The hope is to restore the lookout to make it safe for public visitation. Unfortunately last year’s work party was cancelled due to inclement weather. When the Center called for volunteers again a few weeks ago and I found out some well known fire lookout gurus like Bob Adler, Dave Spies, and Nancy Belt would be present, I jumped at the chance to lend a hand.

An apprenticeship in lookout restoration.

As I’ve been working on the maintenance of more lookouts, especially here in the Methow Valley, I’ve enjoyed learning as much as I can from many of the fire lookout veterans who have incredible skills to pass down.

I spent the day yesterday at Columbia Breaks working side by side with Bob Adler, who is a well-known hiker, WTA crew leader, and long-time Forest Fire Lookout Association member. He had a huge hand in the beautiful restoration of Kelly Butte near Mount Rainier as well as Heybrook and other lookouts.

It was wonderful to meet Bob, chat about lookouts, and receive expert instruction in the art of window glazing. Bob told me that it’s preferable to repair fire lookout windows on a horizontal surface of course, but that’s not always possible. It’s also preferable to replace the entire window with all four single panes but that’s also not always possible. Sometimes you end up piecing windows together a glass pane at at time and that’s exactly what I spent the day doing.

How exactly is it done? Slowly! And very carefully.

First the window frames are treated with a bit of linseed oil, to help protect the wood. Then DAP window glazing is applied around the perimeter of the single pane. DAP helps to create a weatherproof seal around the window glass to prevent condensation and rain from entering.

Once the DAP is applied, the individual glass pane is seated into the frame. Care must be taken not to break the glass, so it helps to spread your fingers, softly work your way around and use a small 2×4 block to push, which distributes the pressure a little more evenly.

Once the window is properly seated, glazing points are added, which are small triangular pieces of metal that secure the glass into the frame. This is also a tedious art that requires using a chisel to carefully wiggle in the points without dropping them. We used three on each vertical side and two on each horizontal side, though we had to get a little creative with one damaged window muntin, which is a vertical piece of wood separating the glass panes. There wasn’t much left to fasten into.

Now the really tedious part begins and I was taught how to add DAP and push it into the window edge with the heel of my hand. If the DAP is either too warm or too cold it can be tricky to work with. Once complete, I then had to use a putty knife to slowly and expertly—or not so much—sculpt beveled edges around the glass and window frame, then remove the excess DAP. Oh, and don’t expose the glazing points while doing this either!

The first few attempts were frustrating but after a while I started to learn the right technique with a few expert tips passed along by Bob. It’s an art, that’s for sure.

Of course I wasn’t done yet. Nope. I also had to go inside the lookout and use the putty knife in a specific way to remove the extra squished out DAP without cutting into the DAP between the frame and window.

It took me almost seven hours of work yesterday to replace all four single glass panes in a single window. Whew! Bob said it’s tedious, slow work that can take weeks. Remember that L-4 fire lookouts have 80 individual glass panes. 80! That’s over 100 hours of work to replace each one if full window replacements aren’t possible.

Anyone who even thinks of vandalizing or breaking the glass in a fire lookout should have to spend a few days replacing fire lookout windows.

Fire lookouts are tedious.

It’s easy to appreciate the history and romance of fire lookouts but once you start down the path of hands-on maintenance and restoration work, that appreciation runs even deeper. Fire lookouts are tedious. Materials and parts are often difficult and expensive to find or require custom carpentry. Many structures are so deteriorated from weather or vandals that nothing quite fits together anymore. Shutters can be broken or bump into railings, doors don’t close, windows and frames are damaged, and the list goes on. Sometimes the problems are exasperated by small ad-hoc repairs over the years that deviate from the original design. Below are three funny photos of work on Lookout Mountain outside Twisp last year that show some of the fun challenges.

There are a lot of little quirks to learn when it comes to fire lookouts. Shutters need to be raised and lowered in a certain order so they overlap correctly. Raising outrigger style shutters often takes three people: one person on tippy toes to valiantly hold the heavy shutter, another to attach nuts onto the eye bolts, and a third to either retrieve the bolts dropped over the side or to wiggle the shutter and curse because the eye bolts don’t actually fit into the shutter holes.

It’s a common joke that the one silly tool left behind will be the one you absolutely need to fix some ridiculous thing that prevents everything else from moving forward. “Oh fire lookouts…” I’ve heard more than a few people moan. It’s also a joke about how many people it takes to open and close a lookout. Answer? It’s a lot!

Fire lookouts are never easy and there’s a reason it took volunteers 140 hours to refinish the door on the Kelly Butte lookout. It’s a labor of love and why vandalism to these structures is so frustrating.

But there’s a beauty in working on these historic structures and paying attention to their details and beautiful craftsmanship. It’s nearly impossible to believe the time and skills that were put into building these structures in the early 1900s on mountain tops no less. What an incredible feat.

I’m just happy and darn proud of my single restored window on Badger Mountain and the great skills I learned!

Thanks Columbia Breaks!

Thanks to the Columbia Breaks Fire Interpretive Center for the lovely day complete with a delicious chili lunch and snacks! It was wonderful to meet Nancy Belt, Dave Spies, Bob Adler, Ray Fischer, Jeff Kimbell, and the other fantastic volunteers who came out to lend a hand. I also got to meet two fire crew members from the Entiat Hotshots and last year’s Methow Valley hand crew who were doing beautiful trail work at the Center and recognized my voice from Goat Peak’s radio last season.

Want to help?

Badger Mountain still needs a lot of work and I’m sure there will be plenty of opportunity to help in the future. If you’re interested in volunteering, contact the Columbia Breaks Fire Interpretive Center. If you’re in the area, consider a visit or even a donation to keep this fantastic center thriving. Follow their Facebook page as well for information on upcoming educational events. Lastly, if you have any interest in fire lookouts, I strongly consider spending at least one day doing restoration or volunteer work on a lookout. It’ll deepen your appreciation for these historic structures that desperately need volunteers to keep them alive. Thanks!