I’ve been a wildlife geek as long as I can remember and friends often joke that if there’s a wild animal around, I’ll be the one to find it. I’ve been incredibly lucky over the years to have seen an extraordinary amount of wildlife including over a dozen black bears, a grizzly bear, a few mountain lions, and even dingos.

Given the opportunity to redo my college education, I’ve often said I’d become a wildlife biologist, which is why I was so excited this past winter to stumble into an incredible volunteer opportunity with Conservation Northwest as a wildlife snow tracker.

I first heard about Conservation Northwest’s volunteer snow tracking project a year or two ago and emailed my interest, but demand is high and spots are limited. Somehow I got lucky and last October I was invited to join the program.

After a winter as a snow tracker, I learned so much not just about animal tracking, but about seeing wildlife and habitats from a completely new perspective. This program has been an exciting and rewarding way to contribute to wildlife conservation right in my own backyard and I didn’t even have to go back to college to do it!

About Conservation Northwest and the Citizen Wildlife Monitoring Project.

Founded in Bellingham, WA in 1989, Conservation Northwest is a 501(c)(3) non-profit conservation organization dedicated to protecting, connecting, and restoring wildlands and wildlife from the Washington Coast all the way to the British Columbia Rockies. Their cornerstone work is the restoration and connection of habitat and they have built numerous partnerships with public agencies, Native tribes, hunters, ranchers, and other conservation groups.

Conservation Northwest’s Citizen Wildlife Monitoring Project, managed jointly with the Wilderness Awareness School, is the largest citizen science effort in North America. The project employs more than 100 volunteers in partnership with state, federal, and tribal wildlife agencies, researchers and biologists, and full-time staff.

Field teams made up of both volunteers and staff operate remote wildlife cameras all over the state from May through October and conduct winter snow tracking from December to March along I-90 near Snoqualmie Pass.

How snow tracking helps wildlife.

The I-90 highway corridor is a critical habitat connectivity area between the North and South Cascades for many species of wildlife. The goal of Conservation Northwest’s winter tracking project is to collect data about the behavior and movement of wildlife along this corridor and also record the presence of rare and sensitive species.

The survey area covers roughly 15 miles of habitat along Snoqualmie Pass from Gold Creek to Easton, divided into 10 transects. Each transect runs parallel to the highway at a distance of approximately 150 meters and is generally surveyed at least 3 times over the winter.

Volunteer teams rotate through transects, walking them and documenting tracks and signs of animals larger than a snowshoe hare. If any rare species tracks are found, such as a wolverine, black bear, or wolf, teams are directed to trail the track immediately. If no critically rare species are detected, teams will choose one track to trail at the end of the survey to document any possible movement in relation to the highway.

Data collected from the project is reviewed by biologists and professionals for accuracy and then exchanged with numerous agencies and organizations that support wildlife conservation. Project data is also being used to inform a series of highway improvements, including wildlife undercrossings and bridges.

These wildlife crossings greatly reduce the number of vehicle collisions with wildlife and offer safe passage not only for land animals like elk, deer, beer, and maybe one day even wolverine, but also for trout and salmon. The first wildlife bridge east of Snoqualmie Pass was completed in 2018 and is the largest wildlife overcrossing in North America.

Becoming a snow tracker.

To become a volunteer, I committed to Conservation Northwest’s required one day training, where I learned the basics of tracking, information about the survey areas and wildlife, and field and communication protocols.

David Moskowitz, a well-known Pacific Northwest biologist, author, and photographer, helps to lead and guide the Citizen Science program and was also present to sell his famed Wildlife of the Pacific Northwest tracking guide. It’s an invaluable resource and volunteers are encouraged to learn as much as they can in their spare time.

At the end of the training day, we were introduced to the experienced field leaders of the project and given an opportunity to sign up with the teams of our choice, forming 4-6 person groups. After exchanging contact information and working out general winter availability, field leaders then went off to determine the winter schedule. Each team generally commits to at least one transect survey each month between January to March or April.

The logistics of snow tracking.

On a typical field day, the team will carpool or meet at the North Bend Starbucks around 7-7:30am. Starbucks keeps all the materials we need for the day in bins: transect maps, clipboards, field documentation, and SnoPark passes. Roles and assignments are decided, which include being the data person entering information into the phone app, the clipboard person keeping a written backup of observations, or the flagging person who makes sure transects are well marked.

Once at the transect, we put on snowshoes and off we go! We traverse the terrain, watching for flagging and keeping our eyes out for anything that might be an animal track. Field leaders are experienced and help share their knowledge of the transects, their wildlife, and tips and tricks for identifying tracks.

When a track is found, we all stop and try to identify it. If we determine it’s legit, we take photos and log information into a phone app about the suspected species, surrounding habitat, snow conditions, and any relationship to the road.

So what’s a day in the field really like?

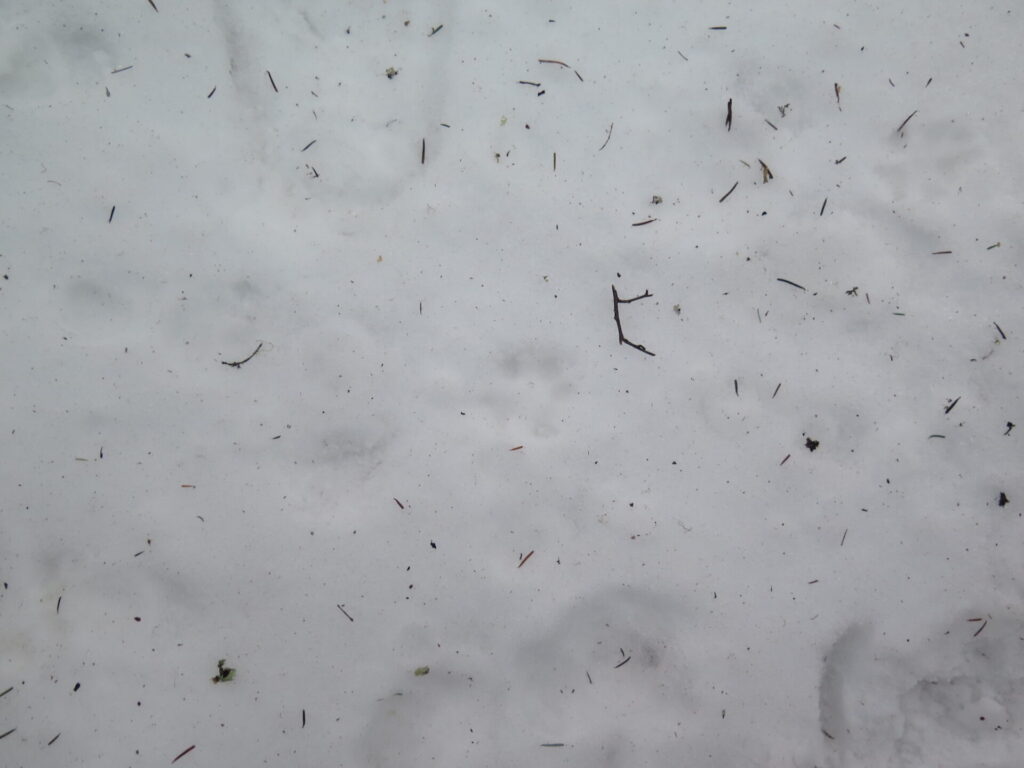

Seems easy, right? Put on your snowshoes and find the tracks! The reality of snow tracking though is something else entirely. You quickly learn that textbook tracks aren’t what you’re likely to find.

Transects are very much off trail and both snow and weather conditions can be highly variable. You could spend most of the day bushwhacking through willows and thickets, crossing freezing streams, crunching around on ice, or buried up to your thighs in fresh snow despite wearing snowshoes.

As far as ground cover goes, you might find firm, hard-packed snow where tracks barely register, sun-cupped snow full of debris, or soft, mushy snow where every plop from a tree above looks like a possible animal track. You might not even find snow at all!

Though my team was incredibly lucky with sunny days for most of our surveys, that’s certainly not the norm and you could be out in rain, snow, or wind, standing still for long periods of time. Warm layers are a must and you’re likely to spend a very long, tough day in the field barely going a few miles.

You might find numerous tracks or you may find nothing at all. Either way, the experience is still incredibly rewarding!

Forensic snow science.

What I found most fascinating about winter tracking was that it was about more than just finding tracks, it was also about uncovering a story. There were multiple times I stood there with my team, staring at tracks, thinking “Whoah, what the heck happened here!?”

Tracking is a thoroughly immersive experience. The more you learn about an animal and how it moves, the more you understand it. Pretty soon you start seeing wildlife and habitats from a whole new perspective.

On one of my first transects, my team found mule deer tracks. Some were very deep and then a few feet away they were barely visible. There didn’t seem to be a huge variation in the snow conditions from one place to the other. How did that happen?

Our field leader explained that the mule deer were probably traveling during different times of the day. The deep tracks would have likely been made late in the day when the snow was soft. The others that barely registered were likely made early in the morning or overnight when the snow was still frozen. “Ah ha!” we all nodded.

Perhaps the mule deer spent the night under the cover of trees, getting up in the morning and moving on? As a lifelong storyteller, I loved trying to figure out the story of these tracks.

Highlights of my snow tracking winter.

My first day in the field we did a transect of both the north and south sides of Gold Creek, which turned into a surprisingly productive and busy day. It took us nearly an hour to make it the first quarter mile of the transect because we kept finding so many tracks! We were out until sunset and by the day’s end had logged numerous coyote, mule deer, and beaver tracks as well as a “suspected” otter track.

On the last survey of the season my team was assigned to a transect on the north side of Easton Hill. Before we even reached the start of the transect we found huge dig areas near the highway with elk bones, which we suspected were from coyote digging through the snow to reach a roadkilled elk.

When we finally left the coyote digs behind and headed towards the beginning of our transect, we were once again detoured by weasel tracks criss-crossing under the power lines. We stopped to investigate and it probably took us nearly an hour to actually start our official transect survey. There was simply too much fascinating activity along the way!

Once on transect, we found an abundance of coyote tracks. We completed our entire survey and then trailed a coyote track for nearly a mile, straight to a den built into the side of a hill. It was a fantastic find!

A deeper understanding of conservation.

I’ve always been an observant person with tremendous respect for wildlife and nature, but participating in this winter tracking program brought me in touch with our backyard wild spaces and habitats in a completely new way.

Sometimes we would be following a single coyote track only to have it suddenly split into two or even three separate tracks. It was fascinating to trail these animals and get an intimate glimpse into their lives through their movements and behavior.

One of Conservation Northwest’s goals with their wildlife monitoring project is to engage and educate citizens. They certainly do a fantastic job of that! At the end of the season, I started thinking even bigger about conservation and how to do my part to lessen my impacts on this incredible planet. Healthy wildlife means healthy water, food, and habitats, which maintain an important ecological balance for all of us.

I loved my experience so much that I also signed up for the remote wildlife camera field season this summer. In fact, I went out on my first expedition near Hannegan Pass in the Mount Baker backcountry recently to help maintain an existing wolverine camera and construct a new run pole, which I will certainly write about soon!

It’s been a dream come true to stumble into this program and it feels really rewarding to give back to conservation and wildlife in areas I truly love. I consider myself incredibly lucky that I’ll be volunteering this summer in my favorite of places, the North Cascades, to help with remote wolverine and grizzly bear cameras.

Want to become a citizen scientist?

Conservation Northwest runs a fantastic volunteer program with adherence to scientific protocol and professional review of all the data collected. There’s no wonder it’s the largest and most successful citizen science project of its kind.

If you’re even a little bit interested in this program, you should absolutely sign up! It’s popular, so you may get waitlisted, but it’s worth the wait. Check the Conservation Northwest website for information about how to become a volunteer as well as photos and season updates.

If you’re a wildlife enthusiast, I would highly recommend picking up a copy of Wildlife of the Pacific Northwest by David Moskowitz. It’s a detailed book that any nature lover can put to good use. David also offers track and sign certifications.

While you’re at it, you should also watch this 30 minute documentary, Cascade Crossroads, about the construction of North America’s largest wildlife crossing, right here at Snoqualmie Pass. It feels great to be part of a project doing such good. Happy trails everyone!